That occurs to me: when I observe: that we still always paint people against a gold background, like the Italian Primitives. People stand before something indefinite—sometimes gold, sometimes gray. Sometimes they stand in the light, and often with an unfathomable darkness behind them1.

1. Rainer Maria Rilke, “Notes on the Melody of Things” in The Inner Sky: Poems, Notes, Dreams by Rainer Maria Rilke, (translated from the German by Damion Searls, David R. Godine Publisher, Boston, 2010).

Since the late 1990s, Éric Nehr has been developing photographic research on the portrait, exploring the notions of alterity and beauty in society.

For this, he chooses male and female models presenting physical particularities, and takes head-and-shoulder photographs of them against coloured backgrounds. He reveals them in their singularity through precise work on light and colour, leading us to take a different view of his models.

There is a highly pictorial dimension in this artist’s photographic work, and his various portrait series have taken inspiration from the history of art, particularly the art of the Renaissance and its old masters, which he has long observed and admired.

For a few years now, he has been photographing people who suffer from albinism, a hereditary disorder characterised by a deficiency is the production of melanin, which makes their vision very poor and makes them photophobic.

These people usually live shielded from light and eyes, but through photography, Éric Nehr counters their disorder and places them back in the light. For the exhibition at the CRP, he will present two series of portraits of albinos, created in various European countries, as well as in Panama, South America and Cameroon, Africa, where they are subject to violence.

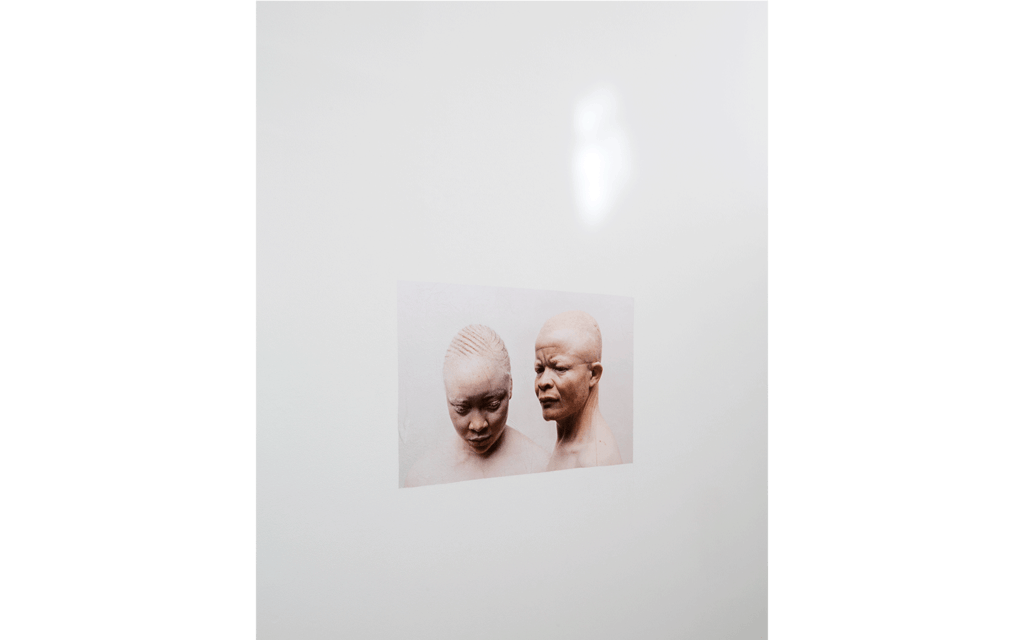

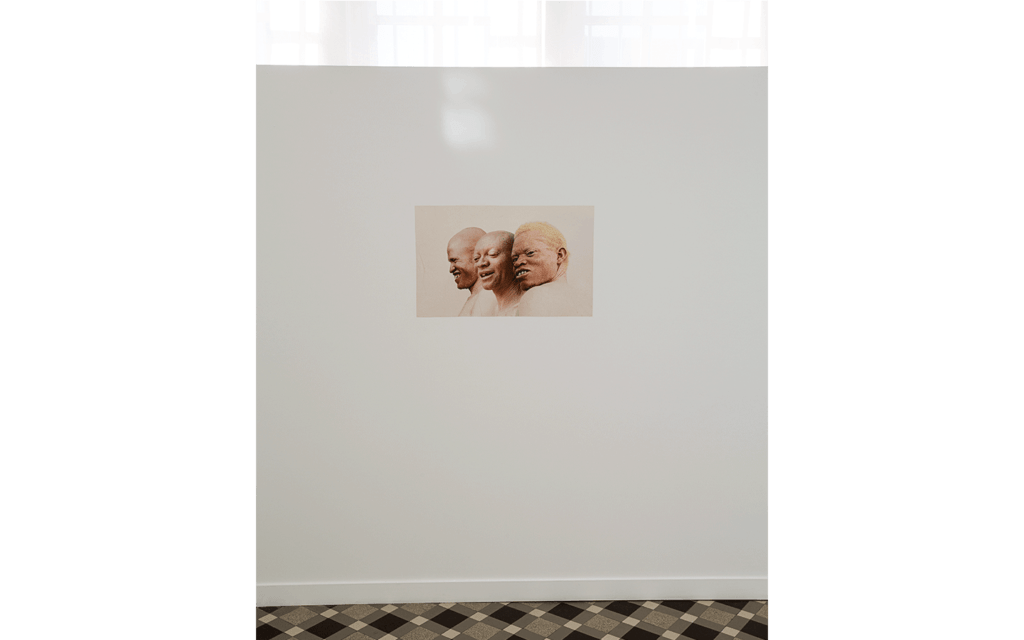

Presented in the main gallery is a first series of images, in the form of wall collages on very thin paper. These are compositions presenting the faces of adult and child albinos, particularly Africans and Indians, whom Nehr met during his travels in those regions. These series of aligned heads displayed on the wall remind me of “grotesque” frescos, in which certain faces have very marked expressions: laughter and sadness that almost seem exaggerated, often taking us into the realm of the bizarre. But a great fragility soon emanates from this series, reflecting the thinness of the paper and its physical vulnerability. These faces delicately emerge from the wall, their humanity restored, appeased, repaired by the second skin that this paper constitutes. The artist created his compositions using different types of light, playing on these variations and producing different renderings: from barely sketched portraits to more fleshed-out portraits with a play of projected shadows.

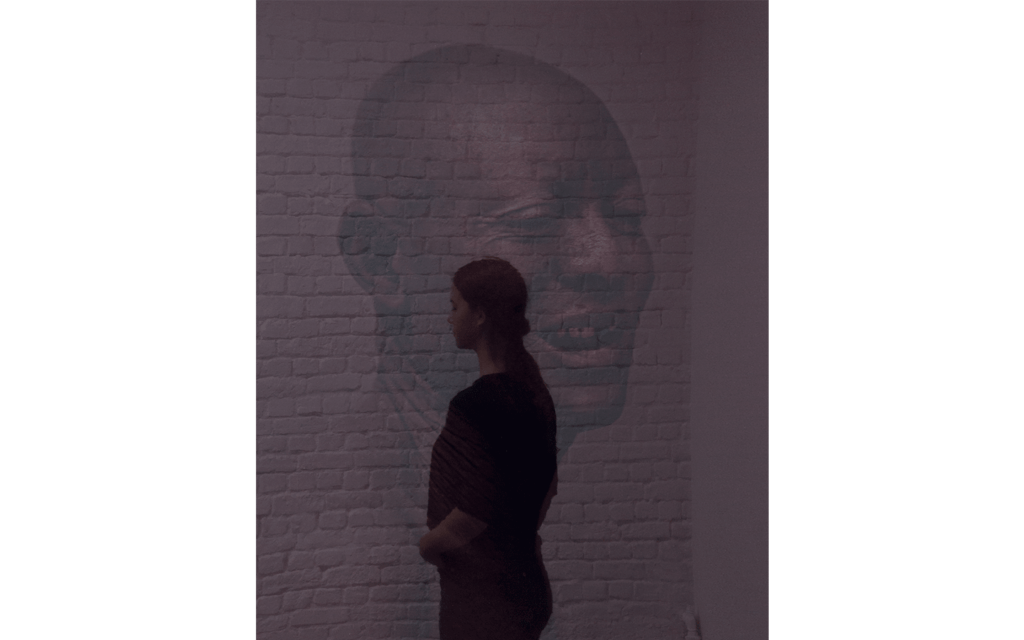

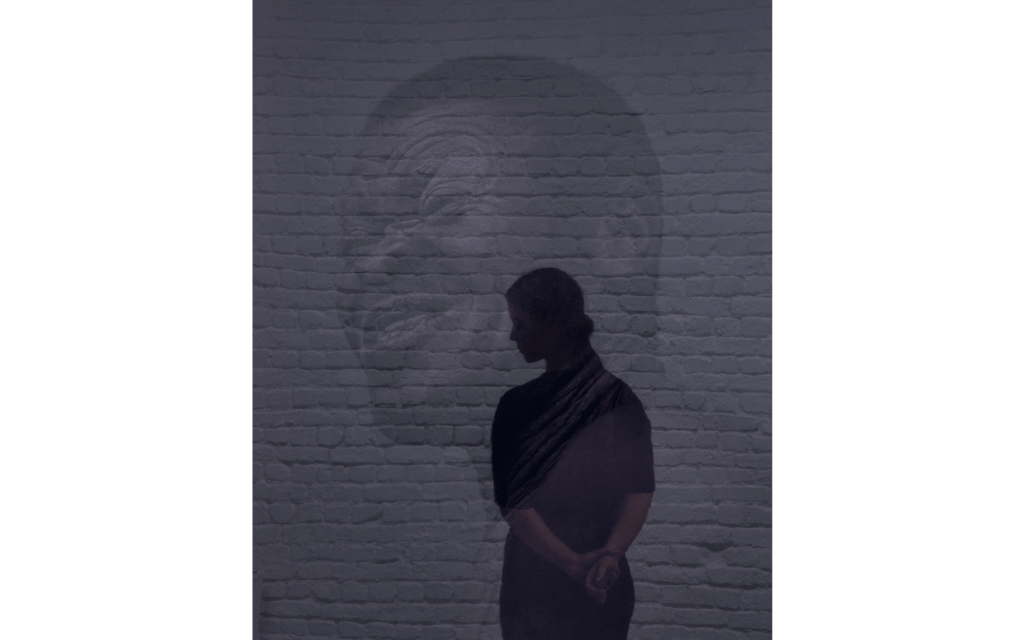

A series of framed photographic portraits presented in the second room echoes the first series on paper. It is made up of underexposed, very black prints referred to as mirrors, which appear as monochromes in which the image does not offer itself immediately; one has to move around to see it. Through this particular treatment, the artist wanted to give the models the black colour they would have had if they had not suffered this disorder, thus erasing this determinism. He also wishes to establish the right conditions for a meeting that is sometimes painful for viewers, appealing to them by referring them back to themselves in their perception of these faces, which bear the marks of time, the accelerated time of illness, and therefore act as “memento mori”:

By erecting dark monochromes on ultra-bright sheets of paper, I place viewers in front of a distorting mirror. Their eyes run up against their own Western image while the contours of the much altered portrait get lost. A bit like a viewer hampered by a painting’s protective glass, we search for an angle, the one that will allow us to submit to the portrait, to its immersion.

By exposing, indeed overexposing these people to the light that is their curse, the artist captures their hypersensitivity and fragility on film, and in the style of the photographic process, reveals an image that momentarily abstracts them from their sufferings and from a day-to-day life that is very difficult, particularly in Africa. But for Éric Nehr, the point is not to show the often difficult reality of these people in a documentary style—recording their state of suffering and placing it back in the context of its objective brutality—but rather to give these models a presence in the world by transcending their handicap in an artistic and aesthetic approach.

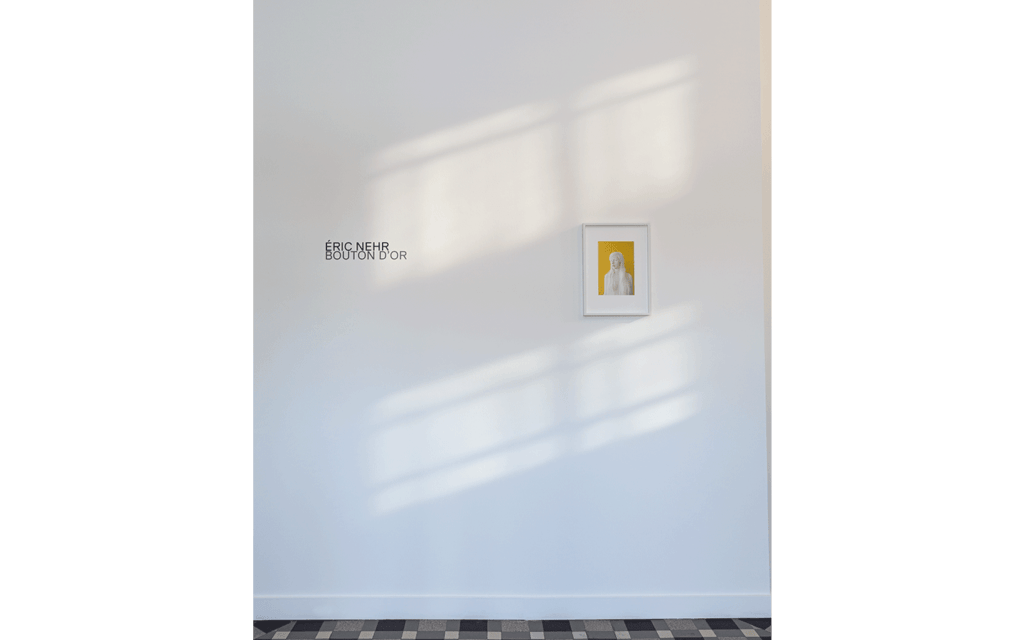

There remains the face of that young woman appearing in all her visual grace and power, like an enigma against a Renaissance-style gold background: “Bouton d’or” [“Buttercup”], who lends her name to the exhibition. Éric Nehr is saying something here about the universality of beauty and the irreducibility of being.

Muriel Enjalran, director of the CRP/